Thank You to Our Heroes!

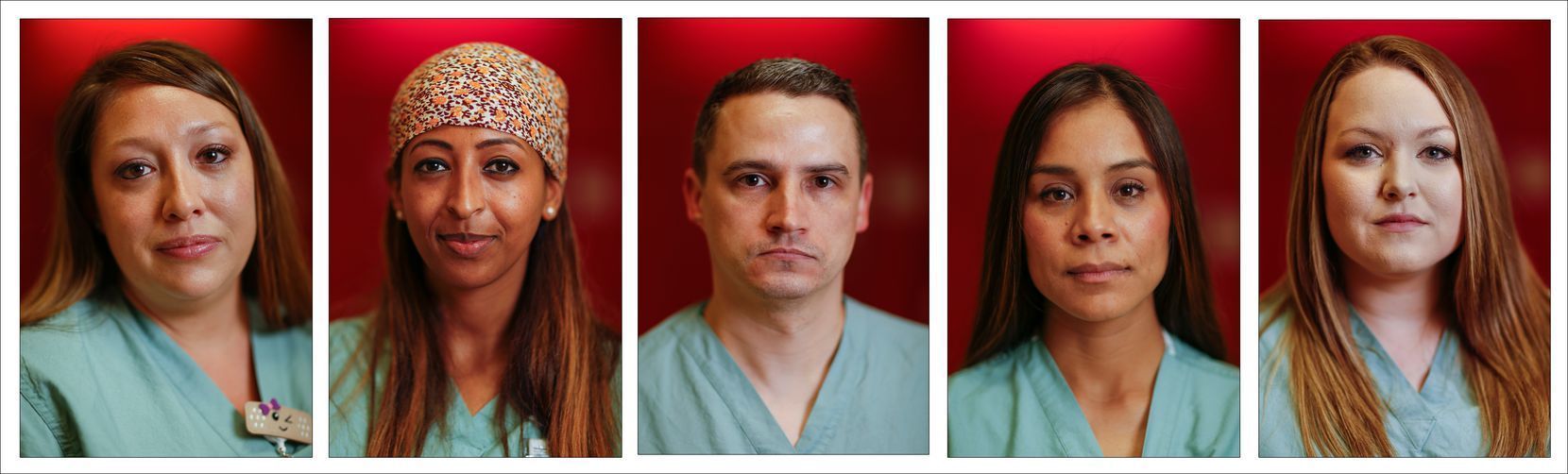

From left: Nurses Shasha Niederhaus, Liyu Daniel, Tyler Brookshire, Perla Sanchez-Perez and Rebecca Berry are pictured in this composite collage photographed outside the COVID-19 Tactical Care Unit at Parkland Memorial Hospital

Today we want to honor Shasha Niederhaus, RN, Liyu Daniel, RN, Tyler Brookshire, RN, Perla Sanchez-Perez, RN and Rebecca Berry, RN, Parkland Memorial Hospital, Dallas, Texas. Here is their story by Sharon Grigsby

One of the nurses has moved into an RV and hasn’t seen her 7-month-old daughter in more than five weeks. Another’s only contact with her 2-year-old has been to don an N-95 mask and gloves for a birthday hug. A third, who lives alone, volunteers for every shift she can get to nurse the most critically ill COVID-19 victims.

These women are among the 300 medical staffers in the Tactical Care Unit — home to Parkland Memorial Hospital’s coronavirus patients — who are making enormous personal sacrifices to do jobs that most of us would turn tail and run from.

The caregivers at work on the far side of the COVID-19 unit’s foreboding entrance — papered with safety protocols and painted red to warn away those without proper PPE — are not just skilled professionals. They are the stand-in family for frightened, lonely patients and the vital communication line between hospital beds and worried, locked-out loved ones.

That means assisting a critically ill man in making the call to family members that would almost surely be his last. Wheeling a just-released coronavirus survivor to her still-ill husband’s room for what the woman hopes won’t be a final goodbye. Placing a cloth prayer card or rosary alongside an unconscious patient kept alive by a ventilator.

“We’re everything to them right now,” nurse Shasha Niederhaus said.

From left: Nurses Shasha Niederhaus, Liyu Daniel, Tyler Brookshire, Perla Sanchez-Perez and Rebecca Berry are pictured in this composite collage photographed outside the COVID-19 Tactical Care Unit at Parkland Memorial Hospital on Wednesday.(Ryan Michalesko / Staff Photographer)

Five Parkland nurses talked with me Wednesday in a conference room just steps away from the red door. In addition to the stories about loss and sadness, they wanted to share what keeps them going: The moments when “Code Happy, COVID discharge,” rings out over the unit’s loudspeakers, followed by a snippet of Pharrell Williams’ jaunty 2014 tune.

“You picked me up from the dust and gave me a new life,” one man rejoiced in Spanish as the medical staff lined up to tell him goodbye.

No matter how many times a day “Code Happy” rings out, “we never get tired of it,” Shasha told me. “It lifts everyone.”

The patients confined to the 116-bed coronavirus hospital within Parkland need that hope.

“It’s so unpredictable what COVID does to people,” said Liyu Daniel, the single nurse who works as many hours as supervisors will allow. “One day they are breathing OK. And the next day they are on a ventilator. And the next day they are really fighting to live.”

Most of Parkland’s third floor, where surgeries take place in normal times, has been renovated into the Tactical Care Unit. As of Thursday, 74 beds were occupied, compared with 63 a week earlier. Among Thursday’s patients, 26 were in the most critical care area, including 19 on ventilators.

Since the unit opened in late March, 329 patients have been treated; 14 have died. More than 200 have been discharged and 28 have successfully come off ventilators.

“People here are just as sick as the cases you read about in New York, but we just don’t have as many,” nurse Tyler Brookshire said, “and we have enough resources to not be overwhelmed.”

Liyu told me it’s easy to become attached to these patients. “We would never replace their families. But we are shaving them, combing their hair. Even if they are intubated, we are talking to them. They are never alone.”

The 32-year-old acknowledged that she still grieves for a man in his 20s who died as she held his hand. Liyu recalled thinking, as a chaplain performed his last rites by phone, “The person I had just talked to a few weeks ago, who is younger than me, is now minutes from passing.”

Many patients within the Tactical Care Unit are capable of making regular calls to family members. Others either can’t manage that or have no phone, so TV screens with Zoom capabilities are wheeled from spot to spot.

“We park the Zoom in front of the bed of a nonresponsive or sedated patient and the family members can interact with one another and talk to the patient,” Tyler said.

Often, he said, the toughest calls are those just before a patient, increasingly unable to breathe, must be intubated in order to be put on a ventilator.

“We make sure they call their loved ones — even those who are struggling to breathe — so they can talk to them, because we know that could very well be the last time,” Tyler said. “In some cases, it has been.”

A health care worker is seen through a doorway in the COVID-19 Tactical Care Unit at Parkland Memorial Hospital.(Ryan Michalesko / Staff Photographer)

Perla Sanchez-Perez, the nurse with the 2-year-old, described how the daughter of a dying patient implored her to let her sneak into the ward where her father lay sedated and intubated, on dialysis and pierced by several chest tubes.

“I promise I will stand in the corner and nobody will know I’m there,” the woman pleaded, but the father’s condition was too unstable.

“We both knew the answer to her request. He passed away right after that,” Perla said, “but his daughter’s words will forever stay with me.”

Shasha spoke of the woman released from the Tactical Care Unit while her husband still fought for his life. Shasha wheeled her to his bedside so she could give him a hug. “She was still crying when she got in the car.”

Nurses from all over the hospital volunteered for Tactical Care Unit duty. On the third floor, they pick up plastic bags filled with their personal protective equipment, have their temperature taken and walk through the red wooden door framed with hand-drawn pictures and words of encouragement. Touches of humor — “KEEP CALM AND EAT COOKIES,” one whiteboard proclaims — butt up against stern instructions about proper N-95 mask use.

On the far side of the red entry, the nurses gear up — hair covering, N-95 and surgical masks, face shield, plastic gown, shoe covers and two pairs of gloves. Except for one or two short breaks, they stay in that hot, heavy equipment for their entire 12-hour shift.

When the surgical gloves come off at the end of their shift, the nurses’ hands are wrinkled and waterlogged from sweat and the plastic gown has to be peeled away from their bodies.

The least critical patients are in the med-surg side of the unit, with each nurse usually assigned to three patients. Those most ill are in the unit’s ICU, where one or even two nurses are assigned to each patient.

“We’re in here fighting — you are running the entire time,” Rebecca Berry said as she recalled a recent shift when an emergency in her med-surg area sent her sprinting down the hall just moments after she donned her PPE.

As she helped to stabilize her patient, “to one side there’s another team addressing a woman with COVID who is preparing to go into labor, and on the other side is a group of people bringing in a new admission,” she said. “It can be easy to get overwhelmed in that situation, but your co-workers make the difference.”

Only three Parkland employees who have worked intermittently within the unit have tested positive for the coronavirus, and their bouts with the disease proved to be minor.

Most people who get it are OK, said Tyler, assigned to the ICU side of the Tactical Care Unit. “But once you get it, you have no idea if you are going to be one of those, or if you are going to be one of the ones that’s not going to be OK.”

Tyler lives in Celina, a 40-mile commute from the hospital. Because he’s now on duty five days a week, he and his wife, the parents of three children, agreed he’d stay in a local hotel except for his days off. He credited his wife for “holding it all together” while she teaches school remotely, helps their two older kids with their own studies and entertains the 3-year-old.

Perla, who works alongside Liyu and Tyler in the ICU side of the coronavirus operation, also originally moved into a hotel, away from her husband and their 2-year-old, in order to protect them and, most of all, her diabetic mother, who helps with child care.

“We see how often patients with diabetes and COVID wind up on dialysis,” Perla said.

Once their family garage was converted into a small apartment, Perla was able to at least live nearby. After five weeks in the Tactical Care Unit, she allowed herself to attend her daughter’s birthday party — wearing hospital-grade mask and gloves.

“I looked forward to that day like you have no idea,” she said, her voice breaking. “That was a birthday present to me.”

She plans to stay on the unit for as long as she is needed “or until my family needs me more.”

Liyu can’t imagine doing anything less than volunteering for as many shifts with the most critically ill patients as supervisors will allow her to take. She might be there 24-7 if they would let her.

“We are constantly asked, ‘Do you need a break from this work?’ But I’m always begging to work even more ... because I don’t have anyone at home who might then be exposed.”

She rarely ventures from her apartment, an isolation that she conceded gives her way too much time to worry about the patients she left when her last shift ended. “I usually can leave my work and my patients when I clock out, but right now I take them home with me every single day.”

Liyu leans on her faith to steer her through the anxiety — reading the Bible, praying and meditating. “My family, church prayer group and Bible study groups are the constant [online] force that encourage and uplift me to keep a sound mental state and also decompress any stress.”

Shasha, who works in the med-surg area, feels lucky that no health issues in her family prevent her from being with her husband and two kids. But she’s steering clear of anyone outside her home, including other family members. When her sister recently married in a small service, she made the tough decision not to attend.

Rebecca, who isolates in an RV in the driveway just outside the house where her husband and 7-month-old sleep, lives for the occasional FaceTime moments and videos that mark her infant daughter’s milestones.

“I haven’t held her in over a month,” Rebecca told me. “That may not sound like long, but it feels like an eternity. ... Even if I do this for another month, it’s a quarter of her life.”

But Rebecca remains strong in her conviction that when she shares this story with her daughter in later years, she too will be inspired to persevere through adversity.

Rebecca is crystal clear about why she’s making the sacrifice: “I’m temporarily stepping out of my day-to-day life as mom so that I can play a part in making it possible for someone to keep their mom — or to help someone say goodbye to their mom.”

Thank you Shasha, Liyu, Tyler, Perla and Rebecca for your commitment, dedication, and compassion for your patients and communities.

If you have a story and pictures of a front line nurse you would like us to highlight on our website and social media, please email them to us at info@helphopehonor.org.

OUR DONORS

-

KFA DJ Ken Ito

KFA DJ Ken Ito